Much has been made about how the video game industry is bigger than both the music and film industries combined (update: it’s now about 2 x bigger).

And yet it still seems so hard for people to take games seriously. When we do talk about games, it’s likely the same old stories about how Fortnite/Call of Duty/Grand Theft Auto is making kids anti-social/violent/addicted to rap music.

Meanwhile, technologists have long been borrowing from the world of game design. From the newly minted 3D world of the ‘Metaverse’ to the the gamified, like-comment-and-subscribe driven ecosystems of the social media platforms.

In an interview with Ezra Klein, the philosopher C. Thi Nguyen explains how gamification has become embedded in the technologies we used every day, from workplace software to online education. He explains that, if the novel is the art form most in tune with our internal world, games are the form connected to our sense of agency. And the application of this game-like logic results in the feeling that:

“Our desires, motivations and behaviours are constantly being shaped and reshaped by incentives and systems that we aren’t even aware of.

So if games, and gaming’s wayward cousin gamification, are so incredibly popular and influential, just how do video games tell stories?

How Games Tell Stories

A game is an activity one engages in for pleasure or fun, often with a set of rules and a set goal.

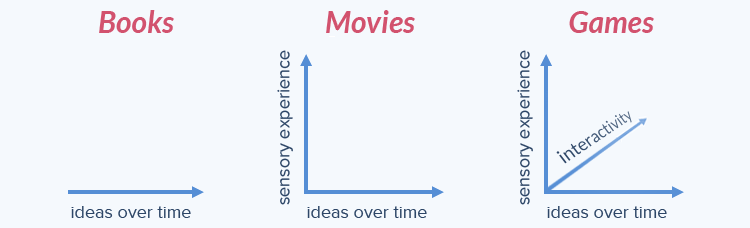

When thinking about how video games tell stories, we can see how they sit somewhere in between a website and a film, in that they’re both interactive and entertaining.

For a long time I thought that more limited games like chess or Tetris, were games sans storytelling. Pure distillations of reflex and problem-solving.

In digging deeper into this world, I found a more holistic understanding of how game-story works by the hosts of Bad End, who outline two types of video games:

Games where the primary author of the story is the designer. Think ‘story-driven’ titles like ‘Red Dead Redemption’ or ‘Firewatch.’

Games where the primary author of the story is the player. Think sandpit games like ‘Minecraft,’ problem-solving games like ‘Wordle’ or strategy games like ‘Crusader Kings’ or ‘Truck Simulator.’

And then of course, there’s everything in between.

On the one hand, ‘Super Mario Brothers’ has a very clear narrative with a single goal: defeat the big turtle monster, save Princess Peach. But the experience of playing the game has little to do with Mario’s unrequited romance. It’s about solving simple problems in an addictive and pleasing gameplay loop: stomping on goombas, eating mushrooms and collecting coins.

The video below shows how ‘Assassin’s Creed’s’ writers and designers map out these sprawling, interactive stories, incorporating overall story and the moment-to-moment gameplay loop.

The Gameplay Loop and Twitch Plays Pokemon

The gameplay loop is the core unit of experience in a game.

In his fantastic book, Theory of Fun, Raph Kostet observe how his children slowly, then all at once, become bored of playing tic-tac-toe. Outlining the delicate balance a game designer needs to strike, he writes:

Games that are too hard kind of bore me, and games that are too easy also kind of bore me. As I age, games move from one to the other, just as tic-tac-toe did for our children.

It’s the goldilocks effect. If a game hits perfect spot between challenging and banal, the player is hooked. You can zone in, enter the flow state and hours of play pass in what feels like seconds.

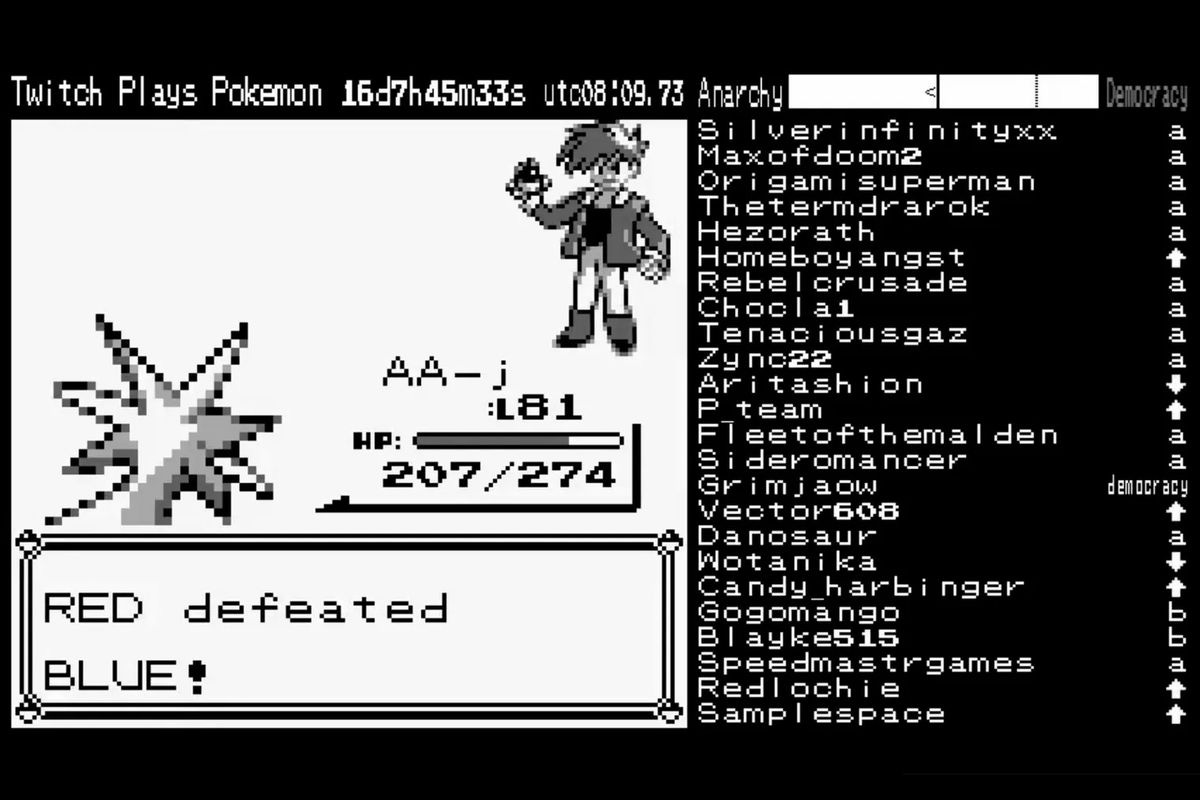

Some may remember the Twitch Plays Pokemon saga.

Billed as a “social experiment,” a bot uploaded a copy of Pokemon Red to Twitch, and users were able to vote in the chat to control the gameplay.

This meta-”game,” saw some factions of the community intent on sabotage and others who wanted to complete the game. Giving new life to a classic title, players spent countless hours attempting to get complete simple in-game tasks.

At the core of Twitch Plays Pokemon’s gameplay loop was the act of play itself. The story became a media phenomena, bringing a flock of new users to the then-emergent platform.

By paying careful attention to the world of video games, and avoiding some of the hazards of gamification, designers can learn which interactions spark genuine fun and enjoyment in their users.

At the end of his interview with Ezra Klein, C. Thi Nguyen outlines his what he sees as the potential danger of a gamified world. He’s not worried about Fortnite and Roblox addicted kids growing up to be violent. He’s more worried about how their exposure to a limited set of highly structured incentives will drive them towards certain behaviours. Asking us to be suspicious of activities that offer too much pleasure, so that we don’t end up participating in a game we don’t even know we’re playing.

This post if part 2 of a series called ‘MetaStructures,’ where I dig into the story structures behind different technology formats. You can read my introduction to the series here.