The Narrative Design of Everyday Things

Introducing 'MetaStructure,' a series on the story structures behind popular technologies

Act One: Into the Woods

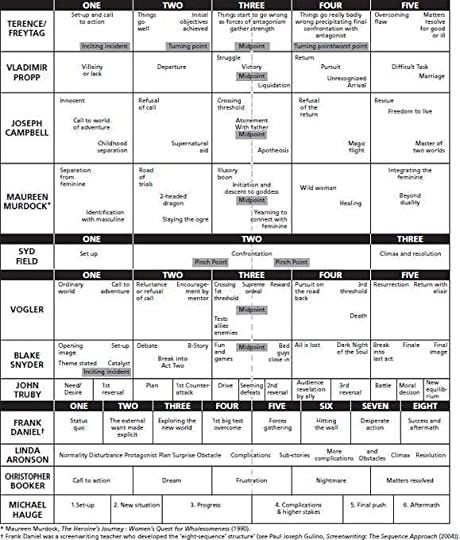

In his book, ‘Into The Woods,’ John Yorke, in one truly monstrous appendix, outlines just a few of the dozens of structures that storytellers have used to understand how narratives work.

Some you might recognise, like Syd Field’s 3-act structure, famously a staple of Hollywood blockbusters. And some of these authors were famous in their own right, like Joseph Campbell who coined the phrase “The Hero’s Journey.”

More than 100 years after the birth of cinema, there exists an obsessive micro-industry that picks apart film and TV structure in minute detail.

From AI that identify story types to the crowd-sourced trove that is TVtropes.

When it comes to film and TV, we have an incredible depth of understanding of just how narratives work on these mediums. The knowledge is out there. And it’s highly democratised.

As I’ve started to think critically about IT, I have noticed how much more opaque processes of storytelling and meaning-making are on these new technologies.

Even as these technologies demand an ever-greater amount of our attention, and artists and designers offer them more of their creative energies.

What is the storytelling structure for our experience of an app? A video game? An immersive VR experience? A social media media post?

Act Two: The Design of Everyday Things

Don Norman, before he wrote the seminal UX book ‘The Design of Everyday Things,’ was an engineer, working in Silicon Valley during the dotcom boom. Asked to help design one of the first laptops, he meticulously considered the build, the materials, how the keyboard felt on the user’s fingers.

But when it came time to test the product, he noticed something strange. People didn’t care about how easy it was to open and close. Or that the power button was slightly sunken into the frame to avoid accidentally pressing it.

They cared about how long it took pages to load. Emails to download. How hard it was to navigate through the clunky interface.

Norman had accidentally stumbled on the field of User Experience Design, and would be the first person to hold the title of UX Designer, at Apple, in 1993.

He realised that people don’t really give a shit about the particular products and services that enable technology, they care about how the experience of how that technology feels.

In this moment, Norman realised that the user was experiencing technology at the level of a story.

And the designers job was to create a product that enabled that story.

I think that this story-and-design-driven understanding can help us dig deeper into popular technologies, to understand their underlying structure. Understanding both how something is experienced, as well as it’s construction, and the tension between these two poles.

Humans are storytelling animals. Story has been with our species from before we developed the capacity for speech. It has a rich history, a deep universality and is uniquely placed to help us understand how technology works on a human level.

How might we use the old to understand the new? How do we map out the story structure of these new forms?

Act Three: Giving Orson Welles an iPhone

A lot has changed since the Lumiere brothers first sent an on-screen train hurtling towards an audience at the turn of the century. Since ‘I Love Lucy’ premiered on TV. Or since Shakespeare wrote ‘Merchant of Venice.’

And yet, in spite of Netflix, digital cinema and the birth of avant garde theatre, the mediums of film, TV and theatre remain basically the same.

If you went back in time and showed Orson Welles ‘Emily in Paris,’ he might tell you to fuck off but he’d basically understand what was happening on screen.

If you gave him an iPhone he’d probably punch you in the nose.

When we look back on our current time in 50, 60 or 70 years, which of our current technologies will feel oddly familiar? How much of this trove of Internet-enabled self-expression will appear to be, not some unique historical abberation, but part of a repeating pattern of human storytelling?

It feels slightly hack, but necessary, to quote to Marshall McLuhan’s 1964 refrain that:

“The Medium is the Message.”

Often derided as utopian and a quack, the real McLuhan was a complex figure. A devoted Catholic and intensely literate academic who didn’t own a TV but worked on Maddison Avenue and cameod in ‘Annie Hall.’

Modern critics often mention McLuhan in the same breath as California Ideology founders like Steve Jobs. Imagining a post-hippy, techno-determinist.

In reading his work and life story, I’ve found the opposite to be true. In an interview with McLuhan’s grandson on The Convivial Society, Sacasas pressed McLuhan Jr. on this point. His response, which I’ll paraphrase, explained that Marshall McLuhan was only a techno-determinist in the sense that he believed profoundly in human beings ability to shape our world.

We hold the reigns to technology, we build it in our image, together. And it’s only by making careful, considered choices about how and why that technology does what it does, that we can seek to change it.

Or, put much more succinctly, by the late David Graeber:

“The ultimate, hidden truth of the world is that it is something that we make, and could just as easily make differently.”

It’s these three frames, Yorke’s analysis of structure, Norman’s design-thinking and McLuhan’s media theory, that I want to keep in mind as I work on this series.

I hope that it’s partly a ‘how to’ for writers and designers, partly a ‘critical analysis’ for an interested reader, and hopefully not too jargon-y.

Across a series of 3 posts which I’m calling ‘MetaStructures’ (okay a bit of jargon) I’ll dig into the narrative structures behind popular 21st century mediums:

0.1: Websites, Apps, Micro-sites and Posts

0.2: Video Games

0.3: Immersive Technology, Augmented Reality and VR

I’ll do this through looking at examples of these technologies in action and following some key players - artists, writers and thinkers - who’ve had an impact across these mediums.

Very nice 👍